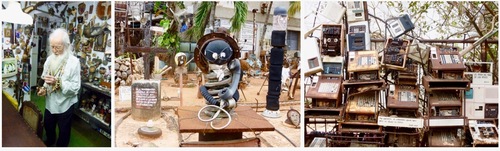

Recently we had a chance to visit Hector Pascual Gallo Portieles (“El Gallo”) - a former barber, then diplomat, now visionary artist/obsessive collector - and his “Garden and Gallery of Affections”, the yard in front and the interior of his humble apartment.

We arrived by public bus with no prior appointment. We asked our way to his front door and knocked. El Gallo, now in his nineties and walking with a cane, opened the door, and with a wide smile he let us into his own world. For the next several hours we walked around in awe of the installations we were seeing, and of their maker.

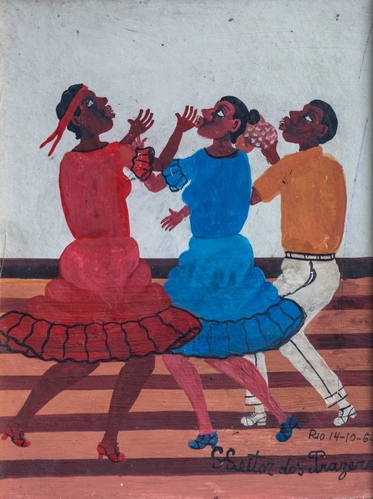

Heitor Dos Prazeres (1898-1966) was a samba musician and self-taught painter in Rio de Janeiro. Son of a military musician and a seamstress, he grew up surrounded by Rio’s Afro-Brazilian music scene which was dominated by carnival. In his late ’30’s he developed an interest in painting and started portraying the life and culture he observed in the streets of Rio’s favelas, including mulatas dancing, people in neighborhood bars, and scenes from the genres of carnival and Rio’s extravagant downtown entertainment district. By the 1950’s he was a known and celebrated “naif” artist whose works today are included in private and museum collections all over Brazil, and the subject of several books and catalogs.

11/01/2018

Death in Mexico lacks the solemn, powerful and funereal feeling that it generally has in other countries, especially in Europe. In Mexico it is part of everyday life. As a common facet of life, it is treated with familiarity and, in a unique way, celebrated. It is regarded as a fundamental part of life, not as the end of existence. Death - of parents and relatives, friends, even animals - is acknowledged and honored by being presented in a joyful, entertaining way. This is a joyous time when for a few hours the souls of the dead are invited back and briefly enjoy the pleasures they were accustomed to in life. These important festivities are equally observed by rich and poor, across all class lines, as people share in essentially private, family feasts - family reunions which include the departed, returning from another world.

10/18/2018

This year the Getty Foundation awarded its first Keeping It Modern grant for a building in Cuba, which is home to an eclectic array of modern architecture. The grant will support research and planning for the preservation of the National Schools of Art of Havana, an educational complex—made of local brick, mortar, and ceramic tiles—that was designed to train Cuba’s young people in “the integration of art, architecture, and landscape in a spirit of equality, freedom, and intercultural exchange.”

To this day much of Guatemala's indigenous (Maya) population adheres to old traditions and belief systems that stem from Pre-Colonial times and incorporate Christian/Catholic elements. This is true particularly in rural areas and it remains the case despite the successful efforts on the part of evangelical sects to supplant Catholicism and all its "pagan" trimmings. One of the most fascinating examples of the strong survival of old beliefs is the controversial character of Maximon.

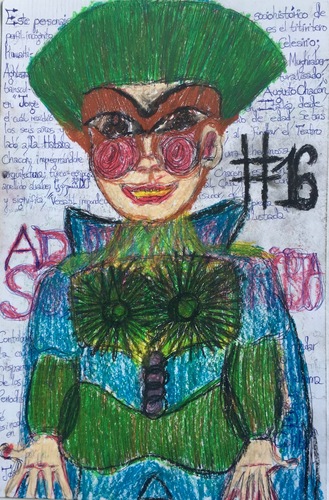

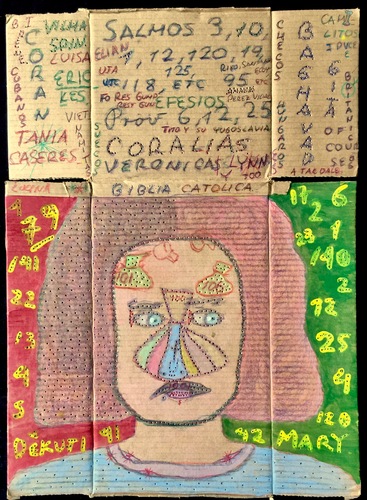

It is not known when during his young adulthood Josvedy started writing and drawing in notebooks, covering every inch of every page with images and dense text controlled by a unique calligraphy and accompanied by symbols and references known only to him. The stories he depicts are made-up fantasies and legends where real historical events are transformed into versions allowing their creator to assume different roles: he becomes a member of European royalty (“Prince of England”) who speaks dozens of languages, a Nobel prize winner, a scientist, an inventor, and so on.

One of our travels through Argentina took us to the northern wine country of Mendoza and San Juan. Apart from visiting wineries we drove around a lot to explore this beautiful, desert-like region with its magical valleys and strange landscapes. We drove by countless little roadside shrines, if that’s what they were. Actually we weren’t quite sure what they were, but they were practically everywhere. Maybe they weren’t shrines, but they were something, and these somethings had plastic water bottles piled high all around them. Empty ones, half empty ones, full ones. Were people just dumping their plastic bottles there? Or were these recycling stations? That seemed unlikely, this being rural Argentina where recycling doesn’t seem to be much of a concept.

On one of our visits to Havana we had an opportunity to visit the internationally renowned Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), a school for visual arts that was formally established in 1976 by the Cuban government on the grounds of a former country club in the Havana suburb of Marianao. Roberto Diago, whose works we have been collecting for some 15 years, took us there. Due to its visionary architecture the ISA is currently being considered for inclusion on the World Heritage list of sites of “outstanding universal value” to the world.

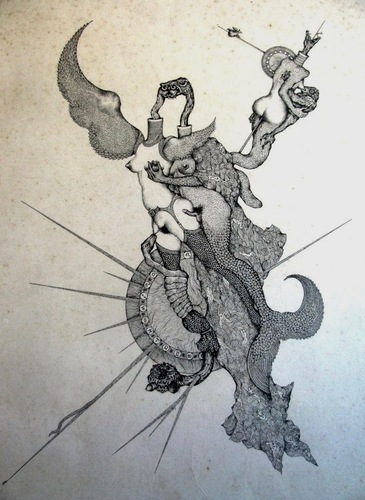

Darcilio Lima had his first art show at 10 years old. He was a crucial player in Rio’s hedonistic underground art scene in the 1960s. He spent a significant period of time in the 1970s in Paris, sleeping in a graveyard. Like any legit surrealist, he was friends with Salvador Dali. And, yet, the Brazilian artist’s name remains widely unknown, despite the captivatingly fine lines and hypnotically twisted figures that ooze forth from the darkest depths of his subconscious. (Huffington Post)

Manuel Mendive Hoyo needs no introduction. We ourselves were long aware of this artist’s extraordinary body of work in the early 1990’s when we visited Havana during the notorious “special period”. He was already an internationally known artist then. Now, decades later, according to Wikipedia, “Manuel Mendive (born 1944) is one of the leading Afro-Cuban artists to emerge from the revolutionary period, and is considered by many to be the most important Cuban artist living today”.

During a recent trip to Havana we decided to visit Mendive’s little town, the sleepy, charming colonial village where he has made his home for most of his life.

08/04/2018

Around the time in Europe (in the 1940’s) when Jean Dubuffet first defined 'art brut' as the creative issue of individuals innocent of and untouched by culture, (what was to be called 'psychotic art' by some), a new notion emerged in Rio de Janeiro, that of images from the unconscious. It has its origins in the pioneering work of a psychiatrist and Jungian scholar — one of the first women to be admitted to the Faculty of Medicine of Bahia in the 1920s.

Carlos Garcia Huergo’s mysterious drawings combine images of human figures, birds or fantasy creatures with letters, names, numbers and mathematical and religious references. He thus creates a universe populated by inhabitants of his own inner environment which includes angels, devils and - always in the foreground - people, surrounded by text and mathematical symbols.

Estape’s attention to detail is as exquisite as his wit. A pink-eared “Exxon” tiger flexes his muscles, a fire-spitting dragon head nestling on his chest. To his right and left caged birds sing sweetly. A spotted leopard-woman, flesh-pink human breasts bare, smiles enigmatically. A curled snake rises up, cobra-like, its forked tongue a mechanic’s wrench. A dignified lady poses in an ornate, layered outfit, but her white breasts are exposed. A wild-eyed woman, short flowered dress riding up above her crotch, is unaware of the saint at her feet. Men are not much featured in Estape’s work, unless – perhaps – in the disguise of monkeys.

As every other country, Cuba has its share of artists who create their works out of the mainstream, far from the academy, unaware of or oblivious to the “art world”, and without the need of an audience or a marketplace. Often mentally disabled or homeless, they tend to work with humble materials including found objects or discarded packaging. Notable among these Havana based creators is Miguel Ramon Morales Diaz (“Ramon”).

Almost 20 years ago, during one of my visits to Salvador, Bahia, I came across an incredible, don’t know what to call it - carnival costume / wearable altar / art brut installation / outsider art assemblage. A dozen and a half years later I lent the piece to a spectacular exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City: When the Curtain Never Comes Down: Performance Art and the Alter Ego. The maker of this incredible work is Raimundo Borges Falcão, about whom not much is known. The exhibition produced a fabulous catalog. I wrote a page about Borges Falcão and his incredible work:

From an essay on Cuban art collecting to a Billboard take on el paquete and the island’s music industry, this season has brought in-depth, thought-provoking coverage of Cuban art and culture. Here are Cuban Art News’ picks for must-read stories, plus a video.

Cementerio Colón is a vast green expanse in El Vedado, Havana’s leafy seaside district. According to Wikipedia, “Colon Cemetery is one of the most important historical cemeteries in the world and is generally held to be the most important in Latin America in historical and architectural terms, second only to La Recoleta in Buenos Aires".

On any regular day locals visiting family graves mingle with foreign tourists and with Cuban pilgrims who flock to the tomb of Señora Amelia Goyri, better known as La Milagrosa, a high society woman who was buried here in 1903 together with her infant after dying in childbirth.

06/11/2018

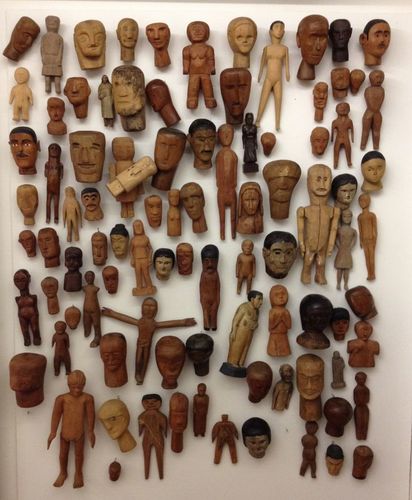

Brazilian ex-voto sculptures - wooden heads, torsos, body parts - represent a special art form without “artists”. Made for generations by anonymous creators, men and women from rural communities who were never exposed to the concepts of art, three-dimensional ex-votos are unique to Brazil’s Northeast (“Nordeste”) - a world synonymous with poverty and backwardness.

New Year’s Eve before last we were in Havana as part of a multi-week Cuba stay (our 10th or 11th in 25 years). We settled into our lovely little apartment on the Plaza del Cristo and were ready for whatever would happen as midnight on the 31st approached.

The balconies up and down and across Calle Amargura, our street, are filled with people. Then comes the moment, and we pop our bubbly. All our neighbors are raising glasses, too (most likely cider), and we all toast to each other, from balcony to balcony. Then comes the first splashing sound, and moments later the entire street sounds like a waterfall for just a few seconds.

Anybody even vaguely familiar with Mexican folk art knows about the Linares family and their paterfamilias, Pedro Linares, who invented a new folk art form in the 1930’s which has been imprinted on Mexican popular arts ever since.

05/22/2018

José Francisco Borges (J. Borges) lives and works in Bezerros, Pernambuco, Brazil where he was born in 1935. He is a self-taught woodcarver, woodblock printer and poet who started as an itinerant peddler of home-made illustrated chapbooks addressing popular themes, folk tales and legends native to the impoverished Northeast (Sertão). This unique art form - "literatura de cordel" (string literature) - consists of written verses and woodblock prints illustrating the rhymed stories. Traditionally, the cordel booklets were sold at country fairs and rural markets where they hung from a piece of string or clothesline.

05/12/2018

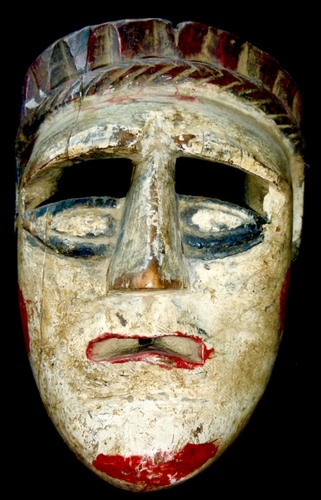

In the rural areas and villages of indigenous Guatemala, masks have long been an integral part of life, binding past and present with tradition, ritual and ceremony. For many generations, folk artists of Maya descent have skillfully carved elaborate masks from different woods, painted in various colors, to be used in choreographed dance dramas. The most apparent quality of Guatemalan masks is their diversity. Although the regional centers from which they originate may be only a few miles apart, the masks are unique and distinct.

Since a Papal visit to Cuba in 1998 forced the Castro government to undo its ban of religious practices, worshippers of all flavors were out in the open again, yet none more so than the adherents of the Yoruba based religion which, fused with Catholic elements, has been practiced widely in Afro-Caribbean regions since the beginning of trans-Atlantic slave trade. Santería, conducted in secrecy during much of the Cuban revolution, had started to bubble up to the surface again.

05/05/2018

To tell the story about how we - that is Michael and I - became friends with Juan Roberto Diago Durruthy, commonly known as “Diago”, I have to tell it backwards.The last time we saw him in Havana, in January of 2017, Diago started reminiscing. How long had we known each other? More than a dozen years, and much had changed. Now that he is an international star in the contemporary art world, he is represented by major galleries, and his works are included in international museum collections and featured by leading auction houses.

José Garcia (“Pepe”) Montebravo was one of Cuba’s truly great self-taught artists, populating his canvases with his famous “Infanta” women, with Afro-Cuban deities, and with winged creatures both human and animal. In many of his paintings turtles, lizards, roosters, blackbirds, fish, dogs, suns and moons intersect with other-wordly characters in human form. The titles of his works are as mysterious and multi-layered as the pieces themselves: Stew of Fantasies, Confused Situation, Time Trapped, Hazards of Memory….

One of the most important deities in the Yoruba pantheon of western Africa is Ogún, god of war and of ironworking, patron of blacksmiths and of all who use metal in their occupations. He continues to rule the spirit world of black cultures throughout Brazil and the Americas. Ogum (in Portuguese) embodies the transformative power and sacred role of iron and as such has given ritual blacksmiths (ferramenteiros) a magical gift.

04/30/2018

In 2005 we went to Cienfuegos, Cuba, for the first time. Our main objective was to get to know several Cuban artists whose works we liked, and visit some art galleries we had heard of. One evening we were invited to a gallery opening somewhere, and afterwards the party shifted to Miguel Angel’s house. Everybody came along, including that terrific musician duo who had played during the opening. Steeped in Cuban musical tradition, they were the perfect team for the occasion.

I met Derek Webster by accident in 2001 when I got lost driving around South Chicago and made a wrong turn. It wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

Each June, thousands of Ecuadorians flock to indigenous highland communities like the ancient village of Pujili in the Andean province of Cotopaxi. The occasion is Corpus Christi, a week-long, boisterous pageant whose highlight is the parade of El Danzante. This festival, celebrated throughout Ecuador’s highlands, is like no other, a joyous pagan ritual honoring sun and earth and harvests blended with Catholic elements.

Victor Teodoro Caceres was born in Tilcara in the Province of Jujuy, Argentina around 1940. His native region is a province in Argentina’s remote northwest populated by indigenous Quechua villages and surrounded by desert landscapes and stunning multi-colored rock formations. Spanish colonial traditions are very much alive there today, along with indigenous cults. For decades, Caceres worked diligently to adapt his town’s Semana Santa (Holy Week) ritual to his own ideas and transform it into something else altogether.