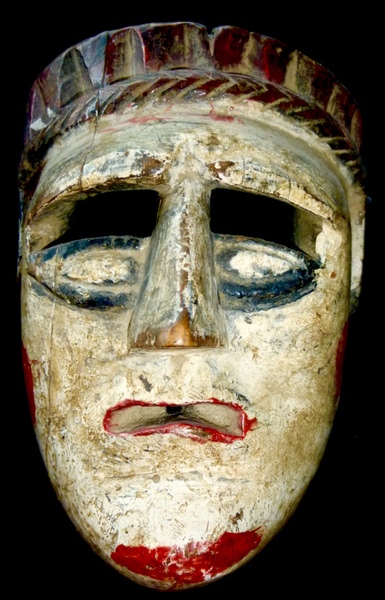

Masks and Their Meaning in Guatemala

5/12/2018

In Mesoamerica, including the area which today is Guatemala, masks can be traced back to the Pre-classic period (2000 B.C. - 250 A.D.) although they may have been used long before. As a vehicles of transformation, they allow their wearers to change both their physical make-ups and their personalities. They can be patron saints, prehistoric deities with the power to heal and do miraculous things, or certain animals with all of their ancient magical powers.

The ceremonial use of masks reaches one of its highest forms in Mexico and Central America, an area marked by its pre-Columbian cultures and its Spanish colonial history. Guatemala has perhaps the richest folk culture still left intact in any country in the Western Hemisphere. The Maya-descendant populations of this geographically dramatic country have preserved much of their native traditions despite the onslaught of many forces threatening them. Even today a simple village lifestyle still exists in much of Guatemala’s altiplano, with villagers following ancient ways. Indigenous life is characterized by a deep appreciation of nature, a respect for fellow people, and an awareness of and participation in one's culture. The relative geographic isolation due to mountainous terrains has created more than twenty different Mayan dialects, along with distinctive mask traditions and costumes identifying the village origin of the wearer.

The Mayas’ involvement in spiritual activity is an intense daily pursuit directed toward their village's patron saint and toward sacred places located in the surrounding countryside. Religion has blended pagan rituals with Catholic traditions imposed on the native population in the wake of the Spanish conquest, and they vary from one village to another. In the rural areas and villages, masks have long been an integral part of life, binding past and present with tradition, ritual and ceremony. For many generations, folk artists have skillfully carved elaborate masks from different woods, painted in various colors, to be used in choreographed dance dramas. The most apparent quality of Guatemalan masks is their diversity. Although the regional centers from which they originate may be only a few miles apart, the masks are unique and distinct.

Villagers generally perform their masked dances for religious/ceremonial purposes. The masks may be made by the dancers themselves or by experienced sculptors working for a specialized dance costume house ("moreria"). The dances, regional in character, include pre-Columbian dances, like the Deer Dance, a ritual hunting dance of ancient Indian origin, and post-Conquest dances, such as the Dance of the Conquest, which depicts the crucial battle in which the Spanish defeat the powerful highland Indian tribe Quiche. Accompanied by marimba music, drums and flutes, they are a form of entertainment, amusement and catharsis in which both performers and spectators take part.

Owners of masks hand them down from generation to generation and may also rent and lend them out. By handing over the mask the owner passes over to the new user the identity of the character in one of the traditional dances which the owner or his ancestors had chosen to represent during their lifetimes.

(For more, read Gordon Frost, Guatemalan Mask Imagery, l976; Guatemalan Masks, The Pieper Collection, l988; Luis Lujan Munoz, Mascaras y Morerias de Guatemala, 1987)

The masks in our collection date mostly from the early part of the 20th century. Please visit the Guatemalan Dance Mask portfolio on our website.